I’m not sure from how far back he came but I was running 16th, my average position while racing at Loretta Lynn’s—a half dozen spots ahead of mid-pack. We were on the last lap of the third moto in a long, hot and dry week in southwestern Tennessee. This kid still had the energy to race aggressively. I battled him hard for maybe a lap but remember, this was almost 30 years ago; I could be stretching the truth to convince myself that it wasn’t just two corners and a straightaway. Riding a Kawasaki KX60 with number 14 on the plates, he pulled up next to me on a set of rollers and we went over the infield tabletop side by side. A kid named Terry Meyer was just in front of us. Even though he was on the outside, he easily beat me to the next corner.

There was something about the kid that interested me (he even hunted down Meyer before the finish). When I saw him stop at the impound area after the checkered flag, I pulled up alongside him. He was wearing bright blue Hi-Point pants, white Hi-Point boots, green gloves, and a white Shoei helmet. I immediately noticed his seat. It was nothing but fabric stapled to plastic. It didn’t seem to contain any foam at all. He was so short his feet still barely reached the ground. When he took off his helmet, his face was serious, pained, and his hair was a mess of matted red curls. I introduced myself.

“Ricky,” he said politely in return. When I looked him up on the results board later that day, there he was, fourth from the top: Ricky Carmichael (4-2-14) for fourth place overall. I was 10 spots further down (11-18-16). If I could have held him off (or had the speed to catch that Meyer kid) I could have finished 13th. I met Carmichael on the track several more times as an amateur, but only when he was putting me a lap down.

This was 1989, the 8th running of the Loretta Lynn’s AMA Amateur Motocross Championship; it featured a mixture of graduates and rookies who all met back up with each other in the future. For Jeff Emig, Steve Lamson, and Jimmy Button, it was their last race before entering full-time professional careers. For kids like Carmichael, Shae Bentley, and Justin Buckelew, it was their first time at the ranch.

The late ‘80s was a different time. Pro debuts following LLMX were not as highly anticipated. Emig and Lamson had actually already been racing pro and each had half a dozen SX/MX races on their resumes. But they weren’t finishing so high that a title at LLMX didn’t still mean something. Emig beat Lamson in the 250 A Modified class, sweeping the three motos. Lamson won the 125 A Modified division while Emig went 31-5-1.

Lamson and Carmichael met up just eight years later when RC handily unseated him as the 1997 125cc Pro Motocross champion. Emig and Carmichael met as professionals in a different capacity: the broadcast booth of the Monster Energy Supercross Championship, a title they each won at least once. And I met up with Ricky quite a few times over the years, including the time in 2013 when I helped produce this career retrospective video for his induction into the AMA Motorcycle Hall of Fame.

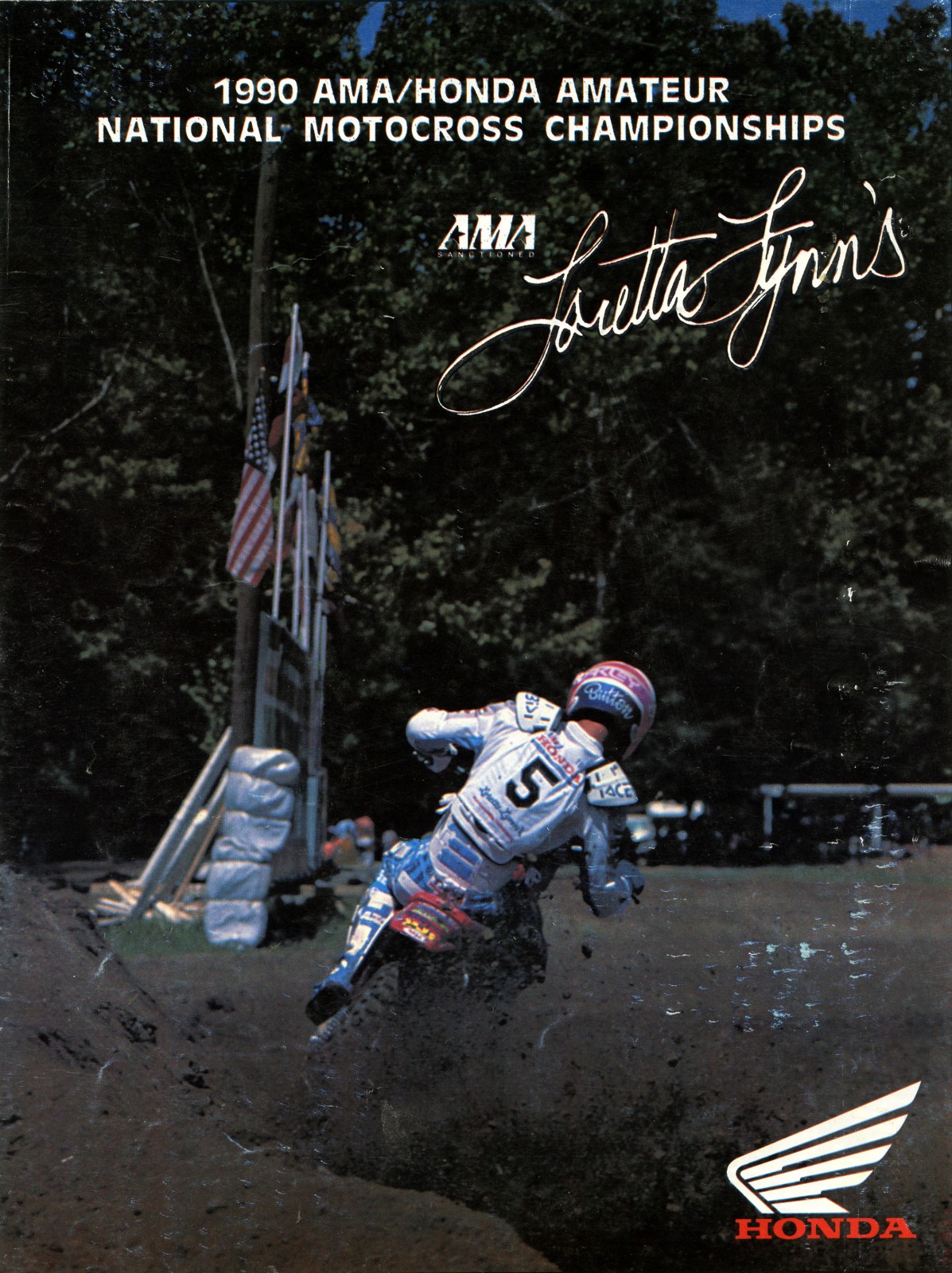

I don’t remember Emig and Lamson battling at Loretta’s back in 1989. Or east St. Louis legend Billy Fosnock or future 2003 AMA 125 title rivals Ryan Hughes and Mike Brown in the 125/250 A Stock classes. Nope. I remember taking a break from the pool or floating down the river to join the crowd at the fence to watch Phoenix, Arizona’s, Jimmy Button destroy the competition in the 125 (12-15) Schoolboy classes, winning all six motos. Wearing tidy looking AXO gear and riding the most factory looking Honda CR125s with a tight #5 on the number plates, the lanky Button rode with such grace, precision and style he barely looked like he was trying. His competition was Billy Schlag, Jim Neese, Jeff Curry, Scott Sheak, Davey Yezek, and a young man from Georgia named Aaron Yates who went on to win AMA road racing championships. "Aaron and I still bump into each other and we talk about how we used to race motocross together,” Button says with a laugh.

Button had turned 16 that June and, to this day, he’s still not really sure why he was racing in the Schoolboy class. He was expected to win both classes in 1988 but came into the week with a shoulder injury and could only manage two fifth place overalls (he did win one moto), while Michigan’s Eric McLear won both titles. In 1989, Button returned to the Schoolboy division with plans to turn pro immediately after. He swept the first five motos with ease but a first-turn pileup in the final race put his perfect record in danger. Sheak led most of the moto.

"I thought 'Damn, I’m not going to win all six.' But I caught Sheak with two laps to go. I wanted to win them all as big as possible. It was a training week for me. I was hammering down.”

Button’s two titles gave him six, the most ever at Loretta’s at the time. His other four titles came in various 85cc divisions between 1984-1987. Notable riders to finish second to Button: Damon Bradshaw, Buddy Antunez (twice), and Colin Edwards (yes, the future World Superbike champion).

Button was going pro and never looking back. No more trips to LLMX. He had been with Honda since the end of 1982 and thought he was being groomed to join the American Honda factory racing team. Even in Tennessee, the newly crowned Camel Supercross and AMA 250cc Pro Motocross champion, Jeff Stanton, was present, doing autographs and spinning laps on the 1990 CR250. Button spent a lot of time with Stanton and the vibe was good. After the awards ceremony, Jimmy and his dad drove immediately to Sherwood, Michigan, where they worked with Stanton.

"We went on this mountain bike ride,” Button says. "It was mid-August. It was hot as hell and we went through these cornfields and streams and he’s talking the whole time and I’m gassed. It was like a recovery ride for him. At that point, I knew I had some work to do in the fitness category. I was not as gnarly as he was.” After a trip to one of the roughest sand tracks he had ever seen, where he watched his mentor pound laps on a CR500, Jimmy’s respect level for Stanton soared.

The Buttons traveled to Millville where Jimmy got knocked around for a 21st overall in his pro debut. A 13th followed a week later in Washougal and then three straight 19th place finishes to round out 1989. "I’d have one good moto and one bad,” he says. What’s odd, and what Jimmy still doesn’t have an answer to even today, is that he came out of Loretta’s feeling like he had the potential to be the next guy. But when they went to the remaining pro races, they traveled in their own motorhome and received no support from Honda.

“We parked in the back with all the privateers. We got no bikes, no parts, no travel money, nothing.” He was expecting to be on Honda’s factory team in 1990, joining Jeff Stanton and Ricky Johnson, and Mike Kiedrowski. For reasons probably left for another story, on November 1, 1989, Button’s Honda sponsorship was cut off. Even two months later, when he put his privateer CR125 on the podium of his very first supercross main event, he received no help.

Later that summer, while Button traveled the country as a privateer, the next class of graduates—including Ryan Hughes, Brian Swink, Jeremy McGrath, Mike Brown, and Doug Henry—were registering at sign up in Tennessee, they received their collectible programs with a distinct image featured on the cover: a lanky Honda rider with #5 on his bib, gracefully blasting a berm.